This page is about David Dyer's lifelong obsession with the Titanic.

A Titanic Obsession

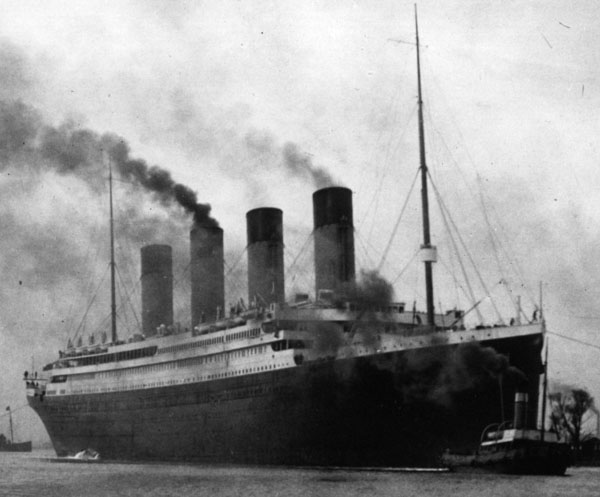

I have been fascinated by the Titanic disaster all my life. When I was four or five years old I watched the classic Titanic film A Night to Remember on television at my grandmother’s house. I was hooked. That ship! I was enthralled by its four tall funnels and slender hull, and by the way it sank: the water inexorably filling one watertight compartment and then the next, the bow settling inch by inch into a black and calm sea. I still think the scene where the Titanic’s three massive propellers rear slowly out of the water is one of the most dramatic in all of cinema. That image said to me as a child: the people on this ship are in big trouble!

Scene from A Night to Remember

Of course, back then the Titanic was not the enormous international industry that it is now. Thanks in large part to James Cameron’s astonishingly successful 1997 film, today there is a profusion of books, DVDs, documentaries, television dramas, websites, Facebook pages, Youtube clips, IMAX movies and 3D jigsaw puzzles. Google ‘Titanic’ and you get 84 million results. The ship has given its name to restaurants, ice-cubes, academic conferences, computer games, plumbers’ businesses, removalists, harbour cruises, calendars and costume shops. But when I was a boy in the 1970s I had trouble finding any material at all. I placed a tape recorder (remember those?) in front of the television to record the audio of late-night repeats of A Night to Remember. I wrote out by hand the Titanic entry in the World Book Encyclopaedia. I read an old copy of Geoffrey Marcus’s The Maiden Voyage.

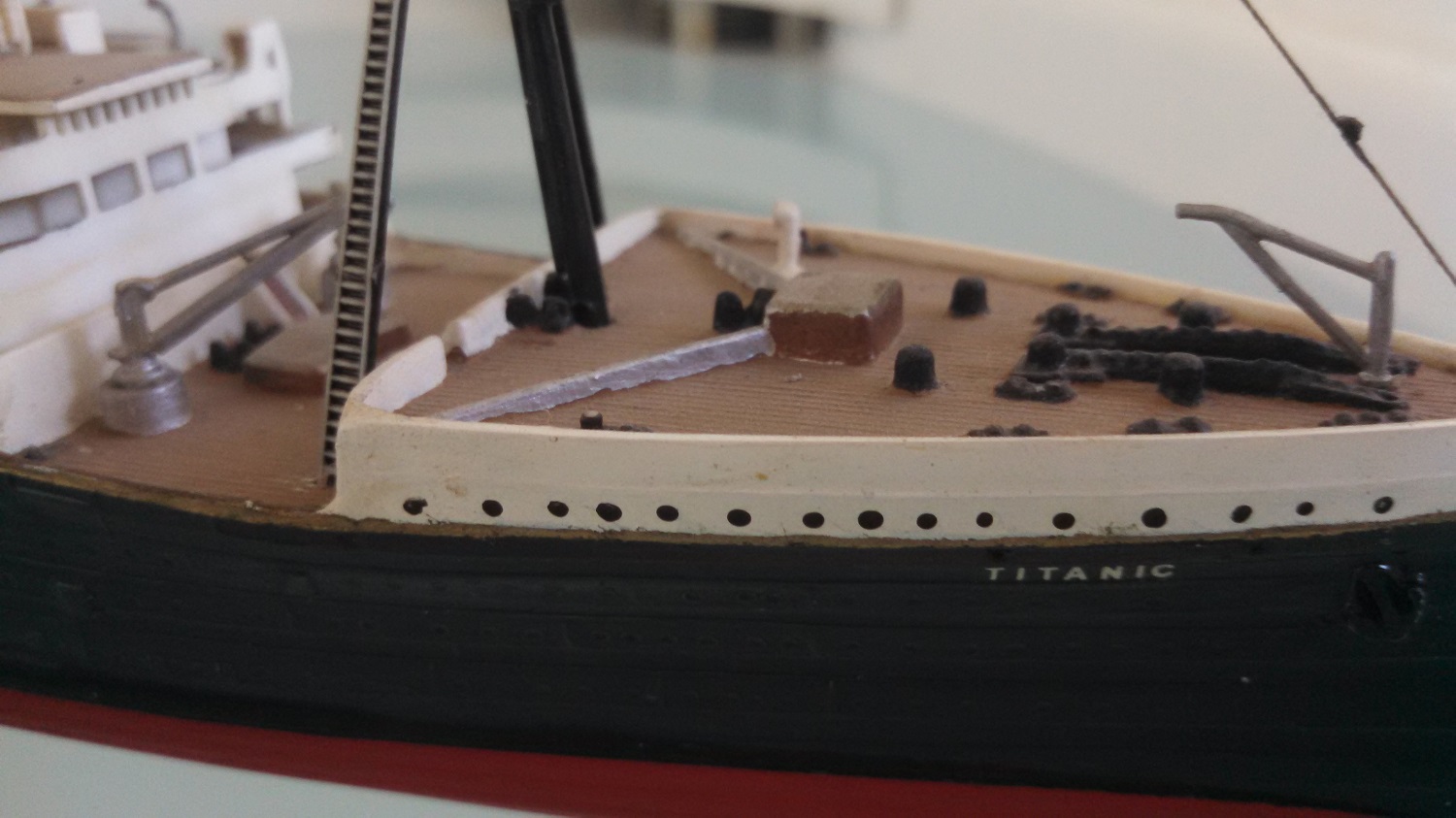

My dad helped me out by drawing for me wonderful pictures of the ship and making me a model. I played with that model so often its funnels fell off. Perhaps one day I will restore it to its former glory.

In fourth grade, I wrote a little novel about the disaster. My mum recently produced it from beneath a pile of papers in a dusty cupboard: five pages of pencilled sentences in one long paragraph. Interestingly, on page 2, it refers to 'the Californian incident': ‘The wireless operator was sending SOS to the Calafornian which was only ten miles away but its wireless was shut down over one hour ago. Rockets were fired every five minutes but the Calafornian thought it was some sort of ship board celebration.’

A shipboard celebration? At 1 am in the morning? On a Monday morning? I know now, of course, that Captain Lord did not really think that. So what did he think? I eventually found out the answer, but not until many years later.

I made a jigsaw, too. It had fifteen hundred pieces: one for each person who died in the disaster. I glued it to a board and hung it up in my bedroom. I also put thick books under one side of my bed so I could fall asleep imagining I was on the sinking liner.

A jigsaw with 1500 pieces, one for each person who died

Later, in high school, I made my own model of the Titanic. I took me a couple of years, because I was determined to make it sink just like the real thing. Back in those days, before Robert Ballard found the wreck, everyone thought that the Titanic sank in one piece. So at least I didn’t have to make my model break in half. After some strategically placed plasticine and internal hull divisions, and lots of practice sinkings, I got the result I wanted. I celebrated by sinking the model in a friend’s swimming pool, using a plastic bag as an iceberg.

Later, in my twenties, I made another, larger model. It sinks just like the real thing too – except it doesn’t split in half. It needs a much bigger tub than my earlier model.

Over the years I have collected many books, papers, photographs, and other Titanicabilia. Two highlights of my Titanic library are a first edition of Marshall Everett’s Story of the Wreck of the Titanic, published within months of the disaster, and a first edition of Titanic and Other Ships (1935) by Charles Lightoller, second officer of the Titanic.

In my thirties, I worked as a maritime lawyer at Hill Taylor Dickinson in London. A few years earlier, HTD had ‘demerged’ from Hill Dickinson, the firm that represented JP Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine in 1912. The IMM owned not only the White Star Line, but also the Leyland Line, managers of the Californian. At the British inquiry, Hill Dickinson instructed Mr Robertson Dunlop to appear on behalf of the owners, officers and crew of the Californian. Mr Dunlop did his very best to defend Captain Lord, Herbert Stone and the others, arguing that it was some other ship that the Californian saw. But to no avail. Lord Mersey found that the Californian very definitely saw the Titanic, watched her rockets, and should have gone to her rescue. ‘Had she done so,’ Lord Mersey said, ‘she might have saved many if not all the lives that were lost.’

Sadly, Hill Dickinson’s papers about the Titanic, I was told, were destroyed during the war. In recent times, Hill Taylor Dickinson has ‘remerged’ to form Hill Dickinson once again.

In 2012 my fascination with the Titanic culminated in my participation in the Titanic Memorial Cruise, which commemorated the centenary of the disaster. We visited the wreck site itself – an experience I will never forget.

Lately, I have been teaching English at Kambala high school in Sydney. But even then I find time to give little lectures on the Titanic!

'Icebergs, Rockets and Martinis' - my talk at Kambala as part of the 2015 Spring Lecture Series